When is enough, enough (and how to establish this)?

…. a tale of guitars, shoes and extended civil restraint orders

So, the thing with lockdown. It’s taken its toll, I’m sure you would agree. Personally, I’ve eaten too much and am shamefully having to moderate what I say to my GP when asked “how many units per week do you drink” (if units were gallons, I’d be fine).

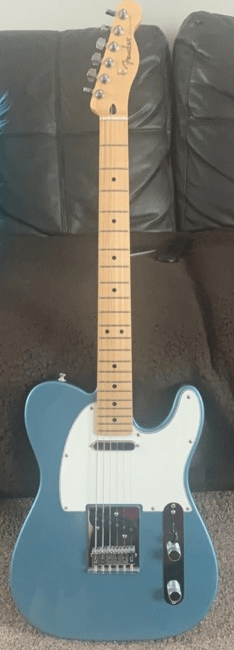

My flexible friend and Prime account have also felt the pressure of lockdown, as has the patience of my wife. Succumbing to one of my frequent mid-life crises recently, I tried to argue in favour of the purchase of a third electric guitar. Using an analogy I thought that would immediately resonate (that she couldn’t accept that one pair of shoes would ever suffice for social sojourn so, ergo, why would one guitar?) I was met with the briefest of ripostes: “TWM. When is enough, enough?” she responded as she departed the room to make tea, leaving me with a feeling of unease at not knowing whether my nuanced argument and flawless analogy had led to her acquiescence or my admonishment. “Too What Means?”, “Touché Wicked Moot”, or was it something else… More importantly, did this mean I COULD buy that Tidal Blue Fender Telecaster!?

In a bizarre moment of serendipity that some may suggest could only come about if I had manufactured the foregoing apocryphal story in a pitiful attempt to humanise myself and shoe-horn some contemporaneous relevance into this article, the etymology of her words were revealed to me in a recent High Court decision. In the case of Thomas Curr v London & Country Mortgages [2020] EWHC 1661 (QB) Mrs Justice Andrews provides some interesting food for thought on the subject of “TWM” – totally without merit – and the impact the omission of this acronym may have on future applications.

Background

Mr Curr was employed by the defendant company, London & Country Mortgages (“L&C”) as a Protection Advisor in 2017. Mr Curr’s employment was governed by a probationary period of eight months which could be extended by a further two months at the discretion of L&C. The contract recognised that his employment had commenced on 18 September 2017 and would continue until terminated. During the probationary period this could be affected by the giving of one month’s notice on either side.

Elsewhere in the contract of employment it was further provided that L&C could, “in its sole and absolute discretion, terminate the employment at any time and with immediate effect by notifying the Employee …. [and making] a payment in lieu of notice…”. Termination was defined as meaning, “…the termination of the Employee’s employment with the Company howsoever caused.”

The probationary period was set out in more detail within the sales-office manual relating to the branch at which Mr Curr worked. The salient points were:

- during the period of probation either party may terminate the employee’s contract on the giving of one weeks’ notice;

- once the probationary period had come to an end, notice periods would be as set out in the contract of employment;

- where the employee’s performance had been unsatisfactory during the probationary period, and it is thought there would be no improvement, employment would be terminated at the end of the probationary period;

- if there was clear evidence to suggest the unsuitability of the employee before the expiry of the probationary period the employee may be terminated early;

- if a decision to terminate before the expiry of the probationary period was to be made the employee would be invited to a probationary hearing and will be offered a right to appeal if such decision was made.

No sooner than three months into the probationary period Mr Curr was invited to a probationary meeting at which his employment was terminated. He was provided with detailed written reasons for that decision and was afforded a right to appeal, which he duly exercised. The appeal was rejected on 9 January 2018. Essentially the reasons for Mr Curr’s dismissal were related to perceived poor sales performance and errors committed following the giving of training and support. Mr Curr disputed the evaluation of his performance and concluded that his employer had treated him unfairly and committed a repudiatory breach of contract.

Unfortunately for Mr Curr he was met with two immediate and seemingly insurmountable circumstances. First, the reservation of an express contractual entitlement by his employer allowing it to terminate his employment on the giving of one week’s notice, whether there was good reason or not (see Johnson v Unisys Ltd [2003] 1 AC 503). Secondly was the simple fact that even if Mr Curr was successful he would be limited in any claim for repudiatory breach to a payment in lieu of notice, something that had already been paid to him.

The High Court Claim

The first claim brought by Mr Curr was for damages based on the termination of his contract and breach of the implied term of trust and confidence. The quantum of his claim he believed to be £1,125,000. This was on the basis that he would have continued to work for his former employer for the next 45 years. Not surprisingly, L&C applied to strike out the claim or obtain summary judgment on the basis of the principle established in Johnson above and Edwards v Chesterfield Royal Hospital NHS Foundation Trust [2012] 2 AC 22.

On 10 May 2018, the application of L&C was heard. Master Cook granted summary judgment and struck out Mr Curr’s statement of case pursuant to CPR 3.4(2)(a) as disclosing no reasonable grounds for success. There is a practical corollary to such a determination and this is set out at CPR 3.4(6). Where a court considers a claim to be TWM, the order it makes must record this fact. The court must also consider whether it is appropriate to impose a civil restraint order at that time.

For reasons unknown, Master Cook did not mark the judgment TWM. He did order that Mr Curr pay L&C’s costs in the sum of £15,000. Mr Curr did not pay and, following a bankruptcy petition by L&C, a Bankruptcy Order was made against him on 24 September 2018.

The Employment Claim

End of the matter you may think. Not from Mr Curr’s perspective. On 13 November 2018 he issued proceedings in the Bristol ET alleging breach of the implied term of trust and confidence and claiming damages in the sum of £1.25 million or, in the alternative, £25,000 being the statutory maximum. Mr Curr’s calculation of damages was based upon the decision in Chaplin v Hicks [1911] 2 KB 786 and on the principle of “loss of chance”.

Employment Judge O’Rourke struck out the claim on four grounds:

- first, the claim was substantially out of time and no grounds were presented for extending time (the claim had been brought nine months after the expiry of the primary limitation period). Consequently, the tribunal did not have jurisdiction to hear it;

- the claim for breach of the implied term of trust and confidence was bound to fail (as Master Cook had already found);

- the claim was an abuse of process under the ET’s own rules of procedure (see rule 37(1)(a) of the 2013 Rules) as it was based upon identical grounds brought before Master Cook that were now res judicata;

- Mr Curr had no status to bring the claim given that he was a bankrupt (albeit discharged) and consequently his right to take action vested with the trustee in bankruptcy. Furthermore, any action taken by the Official Receiver would need to be ratified by Mr Curr’s creditors. Given that Mr Curr’s former employers were his principal creditor it seemed highly improbable that they would agree to action being taken against themselves.

The EAT Appeal

Mr Curr sought to appeal the decision of Employment Judge O’Rourke. No appealable point of law presented itself after a consideration of the papers by Lord Summer, but he did not mark the papers as “TWM” which, under the EAT rules, he could have done. In response Mr Curr exercised his right under Rule 3(1) of the EAT Rules (a request for the appeal to be heard before a judge). This was refused by the judge who recorded that the appeal was ‘bound to fail’. Giving her reasons ex tempore she recorded that there were no arguable grounds for the appeal and that it was reasonably practicable for Mr Curr to have brought his claim in time. Permission to appeal this decision was refused by Judge Stacey. Mr Curr sought an extension to the time allowed to appeal to the Court of Appeal (on the basis that he had not received the written reasons) but this was also refused by Judge Stacey. Aggrieved, and perhaps not surprisingly, Mr Curr appealed this decision to the Court of Appeal where, as I understand the situation to be, it resides.

The Judicial Review Application

On 3 March this year, Mr Curr sought judicial review of the decision of the EAT above and the refusal to grant an extension of time to file his appeal. The application fell before Eady J who dismissed the application and marked it as “TWM” adding that, “although it is not common to state that a claim is made totally without merit, I am satisfied that this is the case in this instance.”

“The High Court Application”

On 20 February 2020, Mr Curr issued proceedings in the High Court basing his claim, again, on loss of chance and the decision in Chaplin v Hicks. The claim was stayed pending the outcome of the EAT decision as to whether the employment tribunal had jurisdiction to hear the claim. On 4 March, the stay was lifted following consideration of arguments from both Mr Curr and the representative of L&C.

L&C applied to have the claim struck out on the basis that Mr Curr’s actions constituted a ‘classic example of an abuse of process’ and also sought an ECRO (extended civil restraint order) against him. Three distinct grounds were advanced in support of the application which are perfectly summarised in the full judgment. Mr Curr, representing himself, countered arguing that in his assessment there was nothing abusive about the five applications and proceedings he had issued against his former employer.

On hearing arguments from both parties, the view of Justice Andrews was that ‘…this claim is the clearest possible abuse of the process of the court…’ adding that, ‘…there is no prospect of success at trial even if Mr Curr were to establish all the facts on which he seeks to rely…’. Justice Andrews determined to provide summary judgment on the application pursuant to CPR 3.4(2)(b) on the basis that this would provide finality to the litigation (she also acknowledged that she would ‘unhesitatingly’ strike out the Particulars of Claim if he felt that this would achieve finality). Justice Andrews also considered Mr Curr’s claim to be “TWM”.

On the issue of the ECRO, however, Justice Andrews was not persuaded to grant such an order. Despite observing (see para 70 and 71 of the judgment) that Mr Curr had, ‘…persistently made claims or issued applications arising from the same set of facts, and airing the same grievances, which are totally without merit…’ she concluded that the question as to whether an ECRO should be made was, ‘…not so easy to answer as first might appear…’. Justice Andrews had also seen correspondence from Mr Curr, sent to the representatives of L&C, in which he sought to, ‘… remind [L&C solicitors] of [his] unfettered power to appeal this case to the nth degree – incurring colossal legal costs for them (which they have no hope of recovering) and meanwhile accruing devastating publicity for them (which I will take delicious pleasure in creating)’.

Justice Andrews accepted that the jurisdiction to make an ECRO had been engaged but was not persuaded that this was the time for making such an order, forming the view that it was difficult to see what new proceedings could be brought. Justice Andrews also observed that it remained open to the Court of Appeal to impose an ECRO if it so determined. Concluding that the Mr Curr’s claim was totally without merit, the application for an ECRO was nevertheless refused.

So, given the extensive litigation chronology surrounding this matter, when will enough really be enough?

A review of ECROs

ECROs are just one flavour of restraint orders that a court may impose under CPR 3.11 and PD 3C, and is generally reserved for litigants who display the hallmarks of such set down in the cases of Attorney General v Jones [1990] 2 All ER 636 and Attorney General v Barker [2000] 1 FLR 759.

When considering whether an ECRO should be made the court will ask itself:

- whether the litigant has persistently issued claims or made applications that are “TWM”;

- whether the litigant would, considered objectively, issue further claims if unrestrained which would constitute an abuse of process;

- what order, if one was indeed imposed, would be just and proportionate to make.

For ECROs, PD 3C 3.1 also provides that an ECRO may only be made where a party has persistently issued claims or made applications that are totally without merit.

There is certainly enough case law on the term to provide judicial guidance on the question. R (Grace) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2014] EWCA Civ 1091, the Court of Appeal determined that TWM means ‘simply bound to fail’. This was confirmed in the subsequent case of Sartipy v Tigris Industries Inc [2019] EWCA Civ 225 where it was concluded that a claim was TWM if there was no rational basis upon which it could succeed.

Under CPR 3.3(7) and 3.4(6) where a claim is struck out as being TWM the court must specify this fact. A similar provision relating to judicial review applications can be found at CPR 23.12. Clearly, in the case outlined above, there were instances where the application or claim should have been marked as being TWM but weren’t. Did this impact upon the course of proceedings generally?

The courts clearly have the ability to consider all claims and applications, despite not being marked as being TWM, in determining whether there a litigant is persisting in their futile endeavor. However, by not marking the claim or application in accordance with CPR 3.3(7), 3.4(6) and 23.12 uncertainty can be introduced. This was noted in the case of Odutola v Hart [2018] EWHC 2260 (Ch) where the absence of the acronym ‘TWM’ introduced uncertainty as to whether or not, collectively, the claims and applications could constitute ‘persistence’.

Conclusions

I’m not sure that I agree with the decision of Justice Andrews as regards the application for an ECRO. On the basis of the facts before the court there was sufficient objective and empirical evidence to support the application made by L&C, in my humble view. Mr Curr had, albeit historically, demonstrated a clear and undeniable desire to frustrate his former employer with the primary motivation being the frustration of his former employer. The court clearly had jurisdiction under the CPR and established case law to impose an ECRO even in the absence of a finding of ‘TWM’. What true prejudice would be caused to Mr Curr in those circumstances? Leaving the proverbial gate open, even marginally, allows an unnecessary uncertainty to persist in this matter, and risks inviting an objectionable litigant to roll the dice for another time.

So, what to do? My view is that, as lawyers with a common purpose to serve the best interests of our clients, it is important to maintain a ‘joined-up’ strategy to deal with potentially vexatious litigants. My view is that the omission in marking earlier claims and applications as being “TWM”, whilst not fatal, certainly did not assist in L&C’s application for an ECRO. Perhaps if, at the time of each hearing, a gentle reminder was offered to the judge as to the requirements of CPR 3.3(7), 3.4(6) and 23.12 as the case may be, L&C’s application would have been bolstered and the ECRO granted. At the very least this simple act would ensure that any subsequent judge was fully informed as to the conduct of the litigant. Such an approach has been recognised as being helpful by the High Court in relation to employment claims. In the case of Nursing and Midwifery Council v Harrold [2016] EWHC 1078 (QB) the High Court observed that it would be helpful if tribunals could make a finding in weak claims as to whether it was totally without merit or not.

It is undoubtedly going to be the case that there will be more litigants in person within the tribunal and court system. The earnestness of a litigant does not necessarily come hand in hand with merit, and being mindful of the above sections of the CPR, and associated case law, is worth retaining in our armory. Perhaps a simple reminder to the judge to inscribe proceedings with “TWM” at the conclusion of a successful hearing, and where circumstances warrant such, might prove to be a very prudent course of action.

PS – my argument succeeded

![Re T (Adoption Hearing: Involvement of Applicants) [2024] EWCA Civ 189 – Court of Appeal on the role of prospective adopters in adoption applications](https://albionchambers.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/CD1-600x400.jpg)